I’m not sure where to start, and I’m honestly not sure where this will end.

I think that sentiment kind of sums up how a lot of people are feeling these days – or, maybe, it’s just me?

I haven’t written a post since April 2024, and there are lots of reasons for that – excuses, mostly. And I’ve missed it, and it’s exacerbated my ability to deal with the challenges and related anxieties life throws at all of us.

To process things I have some strategies – I listen to music, I exercise, I meditate, I have languorous conversations with people I love and I write. What strategies do you use – feel free to comment below; I’d love to hear about them.

I’ve been pretty good about doing the first of four of those things lots in the last year. Right now I’m listening to a playlist a couple of friends and I co-created to help us “keep current” with music; and given some of the subject matter I’m going to write about, the fact that there’s some pretty ‘sick beats’ (that’s still in circulation, right?...Ok boomer!). The other night on a long-delayed flight from New York I listened to playlists with songs my kids have introduced me to; just acknowledging that made me feel lucky and grateful, and smile widely as my fellow passengers grew more frustrated and anxious.

But I haven’t committed myself to writing enough in the last year. It’s been brought to my attention lots, people checking in on a bigger writing project I’ve been in and out of for the last couple of years. I got an email the other day from someone I met at one of the events I attended around this time last year checking in on how it was going. I had a quick wash of shame, followed by some pangs of guilt, but they gave way to more gratitude that people cared enough to ask, to be curious.

And when you offer stories, or share your interest in pursuing stories, I find people generally are curious, and engaged. Almost like they’re cheering you on. At a business dinner the other night in the US South we were swapping stories, and I related some adventures from last Spring on a trip to Vietnam. That was shortly after a close friend called to check in after some deeply-troubling triggers brought all that’s happening in the world right now – particularly emanating out of fortress USA – searingly close and to their doorstep.

It helped us both to talk it through – and where we both were, literally and figuratively – in the world at that moment in time. It was a powerful reminder of the value of the quick check-in – no substitute for the languorous conversation, but a tonic in and of itself – and of the power of story to help us get more proximate at a time when it feels like hugging your people is sometimes the only thing you can do – and maybe, for a moment – that’s enough.

I write to process things (maybe you do, too)? For some reason, putting fingers-to-keyboard, or pen-to-paper, has always helped me to feel more grounded – not necessarily more settled, or ‘better’, but maybe I arrive at a better understanding of some things along the way.

I also get to experience a lot of the world, and it’s something I take for granted too often, even though I try to be mindful and conscious of it. Every time a friend checks in and asks if we can get together, and I respond that I’m currently – or will at that time be – in (insert city/country/continent) – and they reply with “I’ve always wanted to go there”, it sort of smacks my complacent ass a little up the side of its proverbial…head – ok, that doesn’t make sense, but you get the drift from the mixed metaphor there, I hope.

This week I started off on the East Coast of Canada where I live, visited the US South along the border with Mexico while the new US Administration was deploying soliders to the border and putting in deportation quotas, came back through New York where the US Homeland Security Secretary was personally leading immigration raids during Chinese/Lunar New Year celebrations, ventured into Canada’s most export-exposed-and-reliant Province 2 days before threatened US Tariffs could be imposed, before heading back home.

Maybe that seems like a humble-brag, but it’s not intended as such. It’s mostly to help me locate my microscopic interactions with the national and international events swirling around us, and see if I can relate some of what I saw and experienced along the way.

So this post – and, damn, I’ve taken long enough to tee it up…talk about burying the lede – will walk you a dozen or so kilometres through a border city and along Trump’s border wall, zip you through NYC and up to the cold, frozen (great, white) North. Music plays a part, too. Feel free to post links to your favourite tunes below in the comments, too.

Buckle up, it’s a long one.

Happy Sunday.

—

The Uber driver picked me up at my non-descript hotel and dropped me off in downtown Brownsville early on a sleepy Sunday morning. I’d found one of the only coffee shops open that early, and I was keen to make the most of my few available hours to see if I could catch a glimpse of the border Wall, and maybe understand a little more of what it was like to live in this part of the world – particularly in the midst of a flurry of Executive Orders and actions by the new US Administration to deal with the “illegals” and “migrants” it wanted to send packing.

After a coffee I wandered across to the begin to explore the City of Brownsville, which is separated from Matamoros, Mexico, by the Rio Grande River - which became the international border in this area following the 1846 Mexican-American war. Speaking of cartoonish heros and villains – I couldn’t help but hear the voice of the actor playing the villain in the movie Three Amigos who intones he has a plethora of pinatas, when he’s facing down Chevy Chase. The villain’s chief henchman struggles to define what a plethora is, when his boss asks him, but he basically just knows that it is a lot. A few minutes in, and I already felt like this was a place with a plethora of barriers.

In the way we unconsciously mirror one another when talking (when our body language mimics that of the person we’re talking with) I immediately get the impression that this town is in a way a mirror of the ~20 ft border Wall that “protects” it. There are ‘no trespassing’ and ‘private property’ signs aplenty. Everything is fenced, gated, barred and double-barred, or boarded up. The playgrounds, the schools, the businesses, the homes.

The courthouse, a neat and imposing stone edifice in the style of so much of this town — its old forts and military installations, its small houses and its university campuses all mimic the style – sits at the start of one of its top attractions: the 11-mile Battlefields ‘hike and bike’ trail that runs from the war memorial at its front steps, to the plains of “Palo Alto” Battlefield. It’s an origin story, of a sort, because these are the places that the Mexican-American war in 1846 (America’s second bloodiest war, I’m given to understand) triggered the process of turning the Rio Grande into the border in this state.

The Courthouse (with a big sign stencilled on the glass entrance in block white lettering: ‘Weapons Prohibited’) and its sister institution, the US Courthouse I walked past a little later, are among the most well-maintained buildings in town; priorities, I guess. It’s a stark contrast to the proliferation of dingy, sketchy-looking and near-dilapidated bail bond businesses (all declaring - “open 24 hrs!”) that surround the courthouse.

The Wall looms up at the river end of downtown, something like a wooden window blind, casting sunny shadows on the “American side”. I wasn’t quite sure if I could walk right up to it, or if a flood light would shine on me and some voice would warn me away. I saw a man walking along the Wall, with the Mexican customs bureau and a few massive Mexican flags looming in the distance behind him, visible through the Wall.

I walked over to it, and put my hand on it. It looked like a rusted brown drainage grill, or maybe a Barbeque grill – just 20 feet high and turned on its side. I wasn’t electrocuted, and I looked around and hadn’t seemed to attract any particular attention. So I started walking down the wall toward a border crossing.

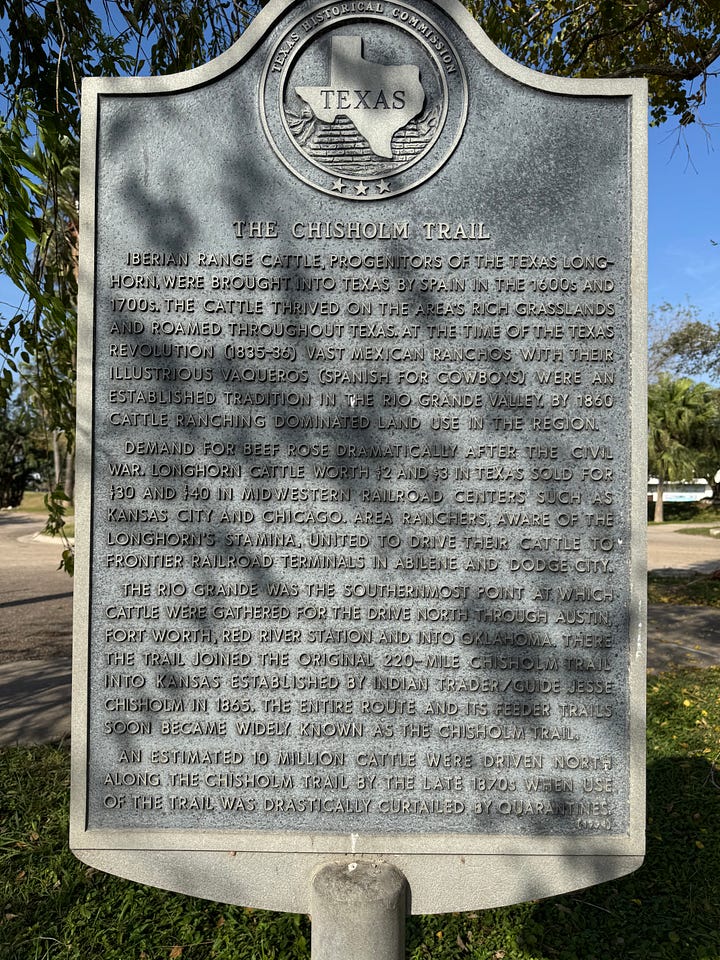

An interpretive sign explained that this area of the Rio Grande - which was flowing about 200 feet behind the Wall from me - was the Southernmost point at which the Texas Longhorn and other varieties of cattle were gathered for the drive north along the “Chisholm trail” – and estimated that ~10 million cattle were driven north along the trail before its use was discontinued.

I recalled reading a news story about the roughly 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the US as of 2022; and somehow the proximity of those numbers just struck me as odd.

I kept walking down the wall toward the Brownsville-Matamoros International Bridge, one of four border crossings between the communities. I walked away from the Wall to the sidewalk, where I had seen a steady stream of Mexican, or Mexican-Americans, walking into Brownsville from the border crossing a few hundred metres away.

They weren’t lugging suitcases, or toting their life’s possessions with them – most just had purses or small daypacks or even just light coats (one young man had a bomber jacket with Korea stylized into the back of it), as if they were on a stroll, going to church, coming to get a thing or two at the local store.

Across the road from the customs point-of-entry buildings in a store parking lot were clutches of families huddled by their car or truck, or beater SUV, looking toward the border crossing; seemingly waiting for someone to come over, come back, or join them. Maybe it was me reading the stoic anxiety into their faces, or their poker faces weren’t as solid as they thought. Given that POTUS 47 was bringing back his “remain in Mexico” policy, and threatening to deport tens of thousands of people a year, under new quotas, the anxiety would be understandable.

It was a hot day and I needed some water, so I stopped into a Dollar General store sitting about 300m from the crossing, which backed onto the Wall. It was stocked full of everyday essentials, directed to a Spanish-language audience.

A Mexican flag was flying beside the cash/till, as if in seeming solidarity – like it was sending a message: I see you. You made it; you’re safe, here. Feel free to engage in commercial trade and all those things so central to the American Dream.

I walked down to the border crossing, looked around at all the infrastructure protecting Us-from-Them, and Them-from-Us.

I turned around and walked back along the Wall in the other direction.

My mind turned to a novel that seared itself into my memory – and triggered me to pick up every other one of Jeanne Cummins’ books – American Dirt.

I tried to remember the name of the protagonists – Lydia, and Luca ? – who are forced into a situation of trying to escape Cartel violence and retribution in Acapulco, so they end up trying to enter the United States with the ‘protection’ of some Polleros/Coyotes – the name given to those who smuggle people across borders into the US.

I remember reading the book shortly after it came out – which was also during the height of a global pandemic. It was the kind of novel that shreds, or roughs up, your soul a little as you sink deeper into the story of the desperate people, doing desperate things so that they can live with adjectives like ‘safe’ and ‘free’ as part of their lives.

In downtown Brownsville there’s a very pedestrian way in which people seem to live with the wall. They habituate to its cameras and gates, and even advertise how to manage if it gets in the way of living their lives (“Stuck? Code won’t work? Call the local office at xxx-xxxx; open 24 hrs”).

If only it were that easy for some of the people who have mortgaged their futures to a coyote, who have left their loved ones, or whose loved ones left them, and are now journeying to freedom in the seemingly vain-hope that the wall - and all its peeps and peeping tech, won’t stand in their way.

I wandered away from the Wall into the downtown core of Brownsville. It feels like everywhere I look I see signs advertising Plasma sales – literal blood money. I google it in the Maps app just to see if I’m just imagining it, but it turns out I’m not. Plasma sales outfits pop up all over the map of the downtown.

I walk past a lot of empty, boarded up buildings, and there aren’t many people around for the first few blocks. Then I start to see families pulling up and jumping out of their cars, and dipping into a series of pop-up churches – offering compassion, and serving food. Come for the food, stay for the word…or, maybe it’s vice versa?

A bald, fully frocked-up Catholic Minister walks past me in the ~22 degree heat, wearing blue jeans underneath the frock, and white running shoes. He smiles deliberately, and cheerfully, seemingly out proselytizing on foot.

I look around and think this town is living in a version of urban development whack-a-mole, with ‘missing teeth’ all over the place, and then some nicer, newer buildings like oases in the urban desert.

I spot some street art, clearly paid for by the city to help distract from the barred windows and long-vacant buildings. Collectively they seem to be trying to will an image of a town long forgotten, or maybe one which never existed here: white picket fence, swing in the yard off the old tree.

Besides the Plasma depots, the most notable retail outlets are the assortment displaying women’s undergarments, bright bejewelled dresses, and quinceanera outfits.

I read somewhere that Brownsville is also home to a SpaceX operation. I had mostly forgotten this factoid until I began to happen upon street art of Elon Musk and astronauts.

There’s an Alanis Morrissette song from the 1990s, Ironic, that still causes debate when it comes on the radio if my wife is in the car with me. She’ll often say “that’s not ironic, it’s just bad luck” when some part of the lyrics are belted out.

That came into my mind as I saw another mural of space and astronauts. I wondered if it was deliberate [and maybe ironic - ?], that Elon Musk chose a border town like Brownsville, with it’s big border Wall and preoccupations over illegal aliens for his space launch base?

Musk’s statements backing deportations and border closures, supporting the campaigns of the German far-right political parties like the AfD go hand-in-glove with a border wall and its attendant technology.

All this thinking was making me hungry, and I began looking around for a place to eat. I passed a handful of ‘higher-end’ restaurants – one, closed on Sunday, offering a French-American cuisine, a busy brunch spot that wouldn’t be out of place in most new condo buildings in any big city, both like green shoots of commerce amidst closed-and-closing looks shops.

I was in the mood for a more home-cooked meal, and I happened upon a populated spot called Arados. It had 60s era window stencils promising “Comida Mexican”. Inside were a handful of families, and what looked like grandparent with their grandies, eating healthy portions of homey Mexican meals. I was definitely the only white or white-passing face in the place, and the only one who spoke English.

I ordered flautas – which turned out to be some of the best I’d ever eaten.

Playing on the TV behind me, so I couldn’t see it but could hear it in stereo, was a movie that talked about a Mars landing; with aliens and secret orders from the President being delivered by agents with secret briefcases. It was in English, and at least one younger patron was mesmerized by the screen, as far as I could tell.

Turns out it was the Transformers movie.

I remember transformers - I played with them as a kid. Optimus prime and all his buddies, battling the Decepticons. When I immigrated from Northern Ireland I did so in a plane, during the daytime, and I did leave an item of clothing behind in an overhead bin - I simply forgot it; I was bummed, but no big deal.

Yet here we were in a town with a border Wall where people ran for their lives, and if they dropped a precious item, or had to slim down their belongings along the way – that was the price of pursuing freedom.

After I fueled up, I walked past another border crossing, and toward the less inhabited areas of town where the Wall ran closer to the Rio Grande river.

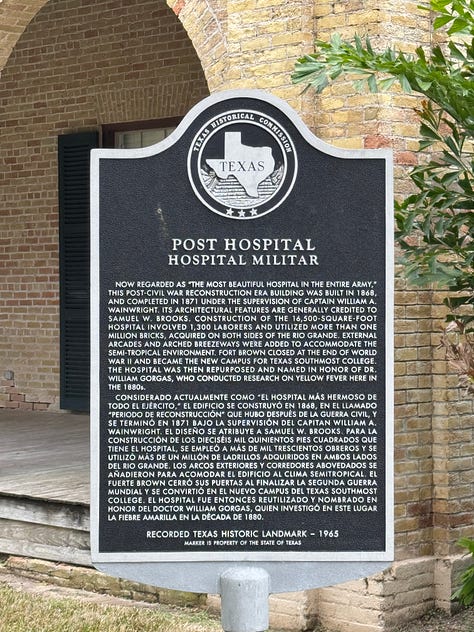

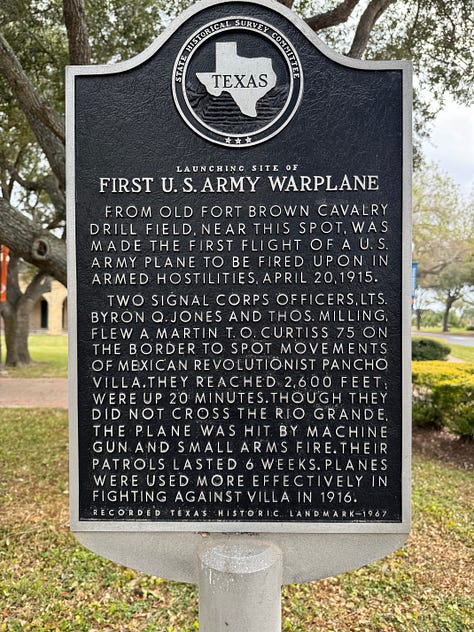

I walked past the Campus of Texas Southmost College – the University of Texas @ Rio Grande Valley (UofT@RGV). Even on a Sunday, empty as it was, it was being patrolled by security in golf carts. The site was formerly Fort Brown, and had seen many notable Americans serve there, and also was the launchpad for the first US Army plane to be fired upon in armed hostilities, in 1915. During a border patrol, in pursuit of Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, the plane sustained gunfire.

As I reached the edge of the campus, I could see the border Wall reappear. It almost bisected the Southmost Scorpions baseball diamond, and ran just behind the athletic complex. I wanted to see a historical marker commemorating the siege of Fort Brown, and learn more about the history of the American-Mexican conflict in this area.

As I approached where my map said the marker should be, at the edge of a now-abandoned Golf Course, two Border Patrol guards on ATVs whizzed down a road off in the distance. Up ahead, I saw a Border Patrol truck. I wasn’t sure what kind of reception I’d get, so I put on my best ‘dumb tourist’ face, and as I approached the truck, it sped off in pursuit of a civilian vehicle that was driving past us.

I kept on heading toward the historical marker. I poked around that area, and walked back toward the College. The curious part of me wanted to walk along the wall here for a while, and get a better sense of the area; I just wasn’t sure if that was a good idea, or how welcome I would be in that pursuit.

The Border Patrol truck was back idling in his previous spot, and I tentatively approached him and gestured that I wanted to ask a question. He rolled down the window, and a twenty-something guy looked out at me in a not-unfriendly way.

Me: “This may sound strange, but I’m visiting from Canada. I’ve heard a lot about the border Wall, and I wondered – can I walk along it, or is that a problem?”

Him: “Don’t worry I already called you in. They all know you’re here; you’re good.”

Me: “So I can walk along this road here, along the Wall…no issues?”

Him: “No issues, I already called you in. You’re fine. But just be aware. Cause, like, you know – I guess the only issue is that stuff can happen.”

I didn’t know what stuff was, although my imagination had ideas. I was nodding my head, and decided to venture out a little further in the temerity department.

Me: “Just so I’m clear, when you stay stuff…”

Him: “You know, if people are trying to come over or whatever, and they are being pursued. A group of guys were walking along a part of the wall earlier and, well, they just weren’t ready when some stuff happened. So, just be ready, that’s all.”

Me: “Ok, thanks. Have a good day.”

Him: “You, too.”

As he was rolling up his window, 2 more Border Patrol officers on ATVs – both in full SWAT gear, whizzed by standing in the ‘bike stirrups’ and nodded with a smile. I watched them zip off down a dirt road into the underbrush, toward the Rio Grande – which lay about 500 metres from the Wall, behind me, at this point.

I walked along, and up ahead was another Border Patrol truck. They seemed to sit every ~500 metres or so along the dirt road bermed-up behind the wall. I didn’t want to ‘stare’ at the trucks, so I began to ease into the experience, and looked around a bit.

Just then I spotted something in the grass beside me. I took out my phone to take a picture, but wasn’t sure how the Border Patrol guy in his truck just up ahead would like that. So I snapped a side angle pic of the sweater which had been ground into the dirt road. I kept walking, and eventually I noticed slippers, socks, torn jeans, and pieces of shirt sleeves.

I wondered how the clothing came to be there. Did those who had been trying to cross to freedom, under cover of night, after negotiating with or navigating the cartels, the Mexican police and border service, the coyotes, the RG river and the walls and border patrol officers, just drop clothing when they are running; trying to get lighter or not have anything loose they could be grabbed by – maybe to try and not leave shoe prints that can be followed, or to prop over top of the fence to help them clear it without scrapes and injury?

At one point, just past an imposing gate in the Wall with cameras, and a length of barbed wire at it mid point to deter people from climbing up it to take advantage of the tree cover on the other side, I looked up and saw a t-shirt at the top of the Wall.

It was sun-bleached, and fixed into the Wall’s tip. I wasn’t sure if it was too high for someone to retrieve it, or if it had been left there as a bit of a talisman. For the guards and those on patrol, a reminder that people would make desperate attempts at freedom, including scaling a 20-foot steel wall. For those seeking to make the attempt, both a sign that you could scale the wall – and maybe also a warning, that you’d lose more than the shirt off your back if you got caught.

Each of the five different Border Patrol trucks I saw over the next few kilometres had Hispanic-American men, in their late 20s or early 30s driving. They all nodded amiably at me, as they either idled at their post, or drove slowly along their route.

I wondered after their job, and how they thought and felt about it – what their pre-and-post-work routines were? Every job has its drudgery, and some jobs are clearly dangerous. For some people, that’s part of the attraction – the adrenaline, the sense of purpose, and the feeling of contributing to the broader safety of one’s community.

It’s among the reasons so many people choose military, or police, service.

Back to the Border Patrol dudes, which seemed to me a different kind hybrid of police and military work – they didn’t call it Homeland Security for nothing.

How did these guys normalize their jobs? Did they exchange messages with friends or family, talking about how boring their days were? Just driving the wall, day was kind of mid. Or, did they share videos of particularly ‘thrilling’ chases, or ‘apprehensions’? Man, you should have seen this one. When they caught families – if they were parents, themselves – how did it feel to have to separate parents and children? Or chase down scared, screaming kids…and, then, try to make them feel safe?

One officer drove past me, down toward the boggy area, and turned around quickly – as if he’d spotted something. He crawled back along the lower dirt road, presumably scanning the dense undergrowth of trees and brush that stretched toward the Rio Grande for “The Illegals” to which the President had closed the border by executive order 4 days earlier.

I wondered, how many people were there actually crouching in the woods on this lazy Sunday morning, waiting for a chance to make their way to “freedom”, or “safety”, or a “better life” beyond the Wall? And did they know they were already, technically, on American soil – even if they were still behind the Wall? Even if they were in the U.S., they weren’t safe, or free, or likely to have the better life they were pursuing.

It made me sad to think I was possibly a few hundred metres from a cluster of people – Coyote or not – huddled there waiting for the chance to ‘run for it’ when the Border Patrol were changing shift, before they could more easily be caught as the patrol used their night goggles and thermal imagers to pick them up and pursue them.

I hit the end of that section of the Wall, at the Veteran’s Memorial Bridge crossing into Mexico, and turned around. By now I felt like all the Border Patrol folks I’d passed, and the cameras I’d been recorded on, knew I was taking photos – so why take bad, half-assed ones anymore? Why not just take pictures of whatever I wanted, and beg forgiveness later?

I walked back along the lower part of the berm, right beside the Wall. About halfway down I had just passed a pair of boots, whose sole was the only thing visible, ground into the dirt at the base of the wall.

I heard some laughter, and I looked up to see a few young women playing a game of Pickleball on the other side of wall. They were oblivious to me, and I had a sense of cognitive dissonance at the normalcy of their lives ~50 metres on the other side of this Wall.

I was nearly back at the College campus, and for some reason a song came into my head. When I was in high school, a friend had a band called the Mere Prophets. He’d recorded some demos on cassette tapes, and I remembered this song from 30 years ago, about teenage angst.

“I’ve been talking to the wall

And I’ve been listening to the floor

Looking for answer for so long

I don’t want an answer anymore

Not listening to what they said

Found out that they just closed the door,

On you

But closing doors are so easy to do”

As I turned back toward town, and waved at the idling Border Patrol agent as I exited away from the Wall, I saw a sign on a construction site at the Southmost College’s sports complex: All Visitors Must Check in at Office.

Now, that, I think, is ironic – right?

Having walked about 12 kilometres along the border Wall, and a little bit into downtown Brownsville, I decided I needed to head back to the hotel. But first, there was one other place I wanted to see – and I didn’t think I should do it on foot.

I approached a cab driver and asked him if he’d take me to my hotel. When we got in the car, I said “but I want to go on a short detour first – into Milpa Verde”. He looked at me in the mirror. I said I wanted to see how the wall bisected that community, and left some houses between the Wall and the River, as this amazing story laid-out in the New York Times, in 2019. I was curious how much had changed.

The story did a great job of outlining some of the trade-offs and consequences of having a wall - at all – but also to be distant enough from the Rio Grande when it flooded its banks.

As we drove down Milpa Verde road into a neighbourhood, my taxi driver turned down a road too early. As we were turning around, he waved at a friend who rents a house in this cul de sac where the fence runs through the backyard – less than 50 feet from the back corner of his house.

We looped down through one part of where the Calle Milpa Verde is bisected by the the Wall, with a break for the road to run through, and the by-now familiar white pick-ups with their green BORDER PATROL decals were sitting off to the left and right, along the raised-gravel Wall road.

I recognized the front porch of the home of Homar, who was in the NYTimes story, and I saw his yard, and that of his 3-4 close neighbours, on the outside of the Wall, but still tucked between the wall and the RG/international border. The road did a dog-leg left and another section of wall lay ahead, and I didn’t notice any border patrol here. I told my driver we could turn around and head back, as he looked a little nervous that I had the window rolled-down and was taking photos as we went.

He turned around and I snapped some photos of the wall as we headed back toward town.

As I looked to my right tucked behind the wall was a Humvee with active duty military sitting on the wheel wells quenching their thirst. They were kitted out in full combat gear and looked straight out of Sebastian Junger’s 2010 war documentary Restrepo, about his embed with the U.S. military forward operating base (FOB) deep in Afghan territory. I remember watching it in my buddy Dave’s basement with a handful of friends, and it feeling very surreal.

An officer looked over at me as we passed, as I began to recognize and have my mind process the scene of a group of warriors I’d seen only in movies sitting behind the wall, a stone’s throw from a poor suburban house; in Southmost Texas. I nodded my head but got a decidedly-less/far less friendly response than from my first border patrol officer in his truck.

These were clearly some of the first of the ~1500 active duty US Military personnel that the President ordered to the border the day after he assumed office.

It was a quiet 15 minutes for the taxi driver, and I, back to the hotel. He was making change for me, and I wanted to give him a decent tip – but he waved his hand and me and said it was fine; feeling like he’d had enough of driving a Wall tourist around for the day.

The next day, after a series of meetings in Boardrooms, our group was taken on a driving tour of the SpaceX facilities – out in the Boca Chica Wildlife Refuge area.

We were told that – speaking of the migration that the border Wall was aiming to stop – a major economic boom in the area is from birders - that group of highly motivated, patient and somewhat pedantic folks who can patiently wait in the camo to catch a sighting of a rare species as it migrates southward, or northward, depending on the season.

There’s an annual festival of birders, and these folks mean business. They now also hold an annual protest of SpaceX because its launchpad is said to disrupt the birds and/or scares them off.

On the drive out to the SpaceX pad, on the only road (the eponymous Boca Chica road), you could be mistaken for thinking it is a road to nowhere, the state it is in. Allegedly Mr. Musk takes helicopters to get there, his Tesla couldn’t withstand the potholes.

As you approach the “Starbase”, there’s a sign in the side of the road - next 2 miles adopted by Starbase Development Corp, and the road condition improves dramatically. The launchpad looms above the cactus and loam/dunes to your left — with the hotels of San Padre Island off in the distance.

An Uber driver told me the previous day that Elon’s presence in the area was a mixed blessing.

When the richest person in the world is your neighbour, it can make some things easier; some harder.

She said on the first launch, their home shook – and it was 45 mins, or 40 miles, away from the launchpad. They woke up at 7am and thought there was an earthquake – a picture frame fell off their wall. Since that launch, they’ve fixed it, she said. She seemed to live with the neighbouring SpaceX facility as a combination of fascination, awe and occasional annoyance.

The $5 million Musk donated to help revitalize downtown Brownsville likely helped.

Yeah, I guess I think it’s cool, she said, finally.

When I asked what it had been like living in Brownsville over the last ~20 years, as the Wall got built, she said her in-laws lived near the wall.

It was bad, before the wall. People would come and hide in cars and houses. One time, my mother-in-law started her truck, and forgot something so she went back into the house to get it. When she came back out, there were people in the truck – migrants – and they asked her to hide them or help them.

That doesn’t happen much since the Wall.

Back at my hotel, I sat down to begin to write out this – now over-over-long piece – and a friend called.

There’d been something happen at work that day, but really they were experiencing a lot of what many of us are absorbing these days – a lot of anxiety, worry, vicarious-and-direct trauma, and just a whole passal of-what-the-actual-f**k-is-even-happening-ness.

We shared some of our day, thanked one another for being on the other end of the line.

The next morning I flew to New York, where I had meetings to attend, before heading North to Canada the next day. As I landed, I was bombarded with news alerts that the newly-confirmed Homeland Security Secretary, Kristi Noem, had personally helped lead immigration raids that morning in the City, alongside ICE officers and all those deputized to help hit Trump’s deportation quotas.

They were targeting schools, food vendors on the streets, as well as known criminals.

I arrived at my hotel, feeling emotionally heavy. The next day I would be back in the great white north.

I checked in, and as I got into the elevator, there was music playing.

It was the Indigo Girls song, Closer to Fine.

I’m including some of those lyrics below, as they rattled through my brain that day. I don’t have good answers for many of the distressing, disturbing and horrible things happening right now in the world. But I do know that checking on your people is maybe one of the only predictable things we can each do – and be open to – in what can feel like dark, and darkening, times.

I'm trying to tell you something 'bout my life

Maybe give me insight between black and white

And the best thing you ever done for me

Is to help me take my life less seriously

It's only life after all, yeah

Well, darkness has a hunger that's insatiable

And lightness has a call that's hard to hear

And I wrap my fear around me like a blanket

I sailed my ship of safety till I sank it

I'm crawling on your shores

And I went to the doctor, I went to the mountains

I looked to the children, I drank from the fountains

There's more than one answer to these questions

Pointing me in a crooked line

And the less I seek my source for some definitive

(The less I seek my source)

Closer I am to fine, yeah

Closer I am to fine, yeah